Granny flats: More popular than ever, but still mired in bureaucracy

by KATY MURPHY

(www.mercurynews.com)

California bills take aim at local red tape

This year, Megan Kellogg’s mother moved into a new in-law unit in her own backyard, freeing up the main house for Kellogg’s family of three. Building it was the easy part. Getting the blessing from a Bay Area city was another story.

“It was horrific,” said Kellogg. “The worst part of the entire process was dealing with the city. It took us almost a year to get the permit. It was awful.”

As sky-high rents and home prices leave people scrambling to find housing they can afford, the development of small, relatively inexpensive homes — known as granny flats or accessory dwelling units — has swelled in popularity with the promise of extra cash or separate living quarters for relatives priced out of the housing market. In California last year, the number of permits issued for granny flats soared by 63 percent compared to the year before, according to an ATTOM Data Solutions analysis of Equifax data published this spring.

But bureaucratic headaches abound, homeowners say, despite new laws that took effect last year to ease local restrictions and shore up the supply of granny flats amid a severe shortage of housing that poor and middle-income Californians can afford.

From lot sizes to parking, cities are “all over the map” with their rules, fees and interpretations of the new state laws governing in-law units, said Karen Chapple, a professor of city and regional planning at UC Berkeley who has a pilot project to grade local governments on their policies.

For homeowners eager to build, the wide-ranging and evolving rules can be a recipe for confusion and unpleasant surprises.

Last year, Francis Schumacher, a retired engineer, bought a house on a large lot in San Jose with a granny-flat project — and his 20-something children — in mind. As he began planning a backyard unit, the city informed him that fire sprinklers were required, despite a new state law exempting granny flats at older homes that don’t have such systems, because of a local rule on any addition of its size. For the sprinklers to work properly, he had to connect them to a water main. The safety feature added $20,000 to the project, on top of $15,000 in other city fees.

“These things kind of really get you,” said Schumacher, who lives in Palo Alto. “That was a surprise to me.”

A sweeping proposal to further slash local fees and regulations on granny flats, Senate Bill 831, was stopped in its tracks late last month in an Assembly policy committee — a victory for cities and counties that protested the proposal as yet another Sacramento attack on local control.

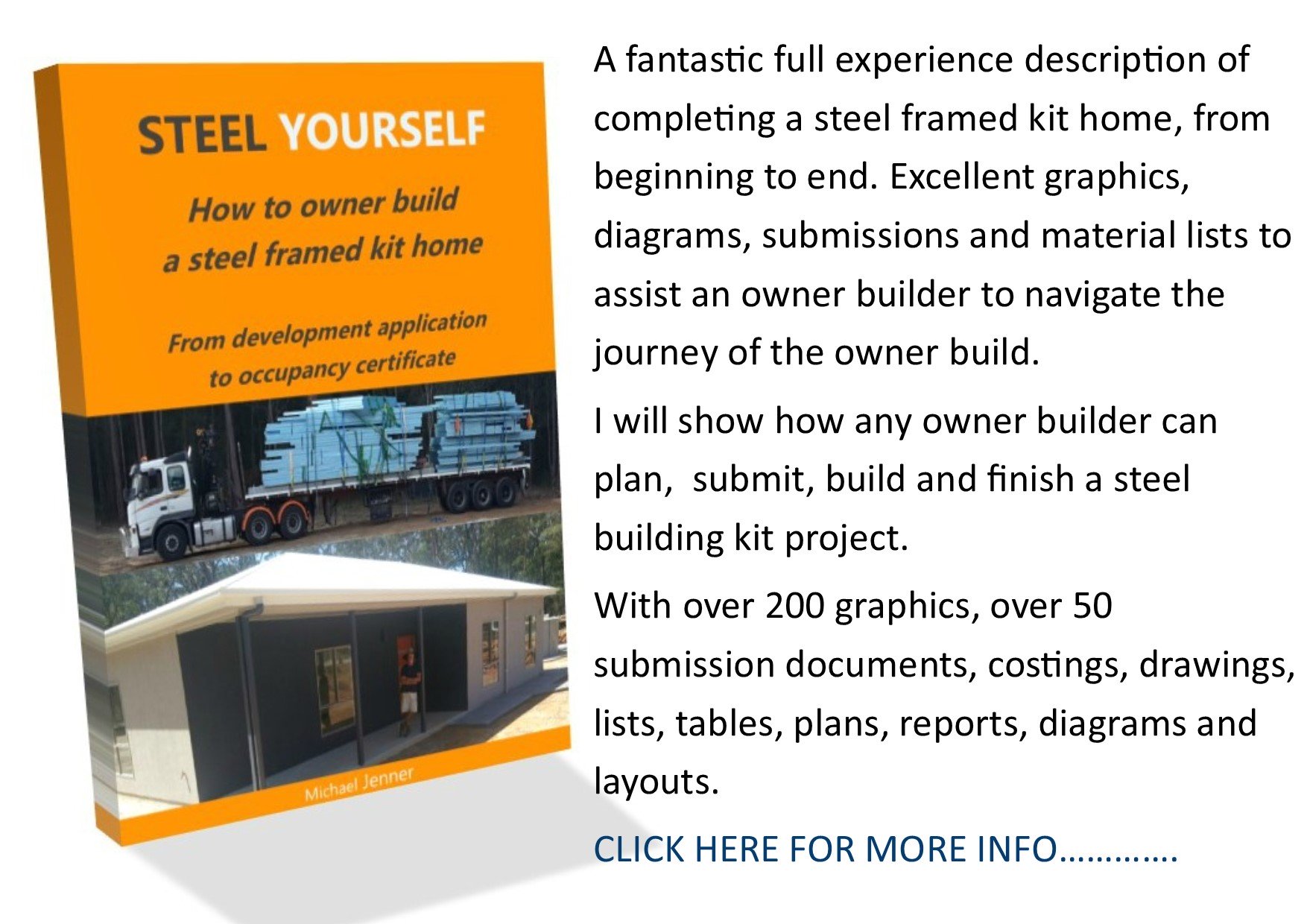

General contractor Curt Hanson (left) and designer Adam Mayberry discuss the backyard in-law unit being built by homeowner Francis Schumacher (back center) in San Jose, Calif., Monday, July 9, 2018. (Karl Mondon/Bay Area News Group)

But the power struggle is not over. Next month the Legislature will take up Assembly Bill 2890 from Phil Ting, D-San Francisco, which would require cities and counties to consider permits for accessory dwelling units within 60 days, rather than 120; prevent cities from banning backyard units on smaller lots; simplify approvals; and strengthen state oversight, among other changes designed to help homeowners.

Also pending is a proposal from Senate Republican Leader Pat Bates, of Orange County, to encourage the legalization of unpermitted units by authorizing local building officials to apply the standards that were in place when the unit was constructed, rather than the latest, more stringent standards. Bates crafted the bill with Encinitas Mayor Catherine Blakespear.

New laws that took effect last year prompted cities across California to rewrite their rules on granny flats. Many are continuing to refine them. San Diego in April stopped charging development fees for new accessory units, and San Jose has just approved changes allowing a second story and, on larger lots, a second bedroom. Campbell is reconsidering its rule banning in-law units on lots less than 10,000 square feet, a restriction affecting about 75 percent of the city’s single-family properties, according to data provided by senior planner Daniel Fama.

The city of Richmond, where Kellogg said she waited nearly a year for a permit, in late 2016 adopted “some of the most aggressive zoning ordinance changes” to encourage the development of in-law units and even tiny houses on wheels, said Mayor Tom Butt. But the city has had few takers, he said — so few that he planned to present the first applicant for an attached in-law unit with a $250 gift card to a home supply store at a city council meeting.

“I’m a huge advocate of trying to increase our housing stock and I’ve just done everything I can to try and accomplish that,” Butt said. “I don’t understand why it’s been so slow.”

The year-old granny-unit laws “cut out a lot of paperwork” and have worked wonderfully for his district, said Republican Assemblyman Randy Voepel, former mayor of the San Diego suburb of Santee — the lone member of the Assembly Local Government Committee to voice support for Sen. Bob Wieckowski’s failed SB 831.

At the hearing, Voepel rattled off a list of groups the bill would help: veterans, seniors, the disabled, and millennials.

“We don’t have many basements in California, so you can’t make that joke,” Voepel quipped. “But there’s a lot of millennials in the spare bedroom. This gets them out of the house and gets them somewhere else.”

But cities and counties are not keen to deal with another set of state mandates just as the ink has dried from the last changes. “I don’t think the folks at the state have any idea how long it takes to draft, vet and implement a new ordinance,” said Christina Horrisberger, a senior planner for Alameda County, who stressed that she was speaking for herself personally and not the county when she said she was relieved that Wieckowski’s bill failed.

And some residents are wary that unfettered growth of second units will lead to yet more short-term rentals and competition for street parking. Jimme James said the Oakland neighborhood where her family has owned a home for decades is “unrecognizable,” with landlords renting out houses at rates that few families can afford.

Three-quarters of Concord residents fear eviction, new survey says

Why home renovations could get more expensive this year

Jake Decker thinks local land-use restrictions are partly to blame for the run-up in housing costs. He and his partner spent six months waiting for a permit to build a 392-square-foot granny flat behind their house on the Oakland-Berkeley border, which they are renting to friends who recently moved to the area. The permit finally came through, he said, shortly after his councilman made a call to the city.

Decker considers it well worth the hassle. Even after cutting their friends a deal on rent, he said, the rental income was enough to let them refinance to a 15-year mortgage on the main house. “We got stupid lucky in this whole thing,” he said.

GRANNY-FLAT BILLS

Quicker approvals, more oversight: Next month, the state Senate will take up Assembly Bill 2890, by Assemblyman Phil Ting, D-San Francisco. It would give cities and counties 60 days, rather than 120, to consider accessory dwelling unit permits. It would also further simplify approvals; prevent governments from banning backyard units on smaller lots; and strengthen state oversight of local ordinances. It would still allow cities to require the main house to be owner-occupied as a condition of approval, as they can now.

Legalize them: Senate Republican Leader Patricia Bates, of the Orange County suburb Laguna Niguel, wants to bring unpermitted units “out of the shadows.” Senate Bill 1226 would authorize local officials to apply the building standards in place when a granny-flat was built, rather than holding it to the latest, more stringent, standards.

Maybe next year? This year’s most far-reaching bill to cut restrictions and fees for granny flats, Senate Bill 831, failed late last month in an Assembly policy committee. But Sen. Bob Wieckowski, D-Fremont, vows to return next year with similar legislation. Wieckowski carried another major bill to promote the growth of backyard units that took effect in 2017.

Join in and write your own page! It's easy to do. How? Simply click here to return to News portal.